Marketing and communications professionals at financial firms face a challenge. They understand the importance of well-written content that follows style guidelines to be reader-friendly. However, they often depend on experts outside the marketing department to generate that content. Investment and wealth management professionals may not know or care about style guidelines. When they fail to abide by style guidelines, they create headaches for their readers and their colleagues.

How can marketers get cleaner copy from their colleagues? This is essentially what one reader asked me in the following message:

How can we implement and maintain style guidelines across a company, generating and maintaining buy-in and compliance?

I brainstormed with some colleagues and took inspiration from Switch, a book by Chip and Dan Heath, to suggest steps to improve your colleagues’ compliance with style guidelines.

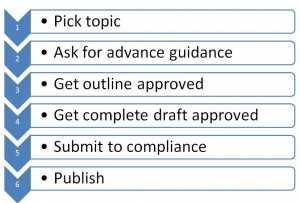

1. Offer style guide training

Ignorance is bliss. At least, that may be true for your colleagues. They can’t abide by guidelines of which they’re unaware.

Provide training on your style guidelines. A short session focused on the most important guidelines will probably attract the greatest attendance and get the best results.

Consider folding your discussion of guidelines into a broader discussion of how to write better or faster. The topic of style guidelines doesn’t excite most people. However, improving one’s skills as a writer helps to build the student’s ability to influence people and advance his or her career.

Hiring an outsider to deliver training can spare the marketing department from playing a bad guy role as an enforcer. Plus, you can exploit the authority of an outsider who knows your industry. Check out my training options, including my webinar on “How to Write Investment Commentary People Will Read.”

2. Make your style guide easily accessible

Make it easy for employees to find your firm’s style guide. This may mean putting it on a shared drive so everyone can access the most recent version.

If you lack a shared drive, consider regularly circulating the most current version with a note highlighting the guidelines that are most important to your firm.

3. Provide different levels of detail, depending on the audience

Your typical financial professional will not use a long style guide that the marketing department views as an essential tool. It’s too much information. It’s overwhelming.

Instead, give your firm’s financial professionals a short document that highlights your most important style guidelines.

Another possibility is to offer them a checklist for reviewing their work before handing it in. My Financial Blogging book includes a checklist that can be customized to an individual writer’s needs.

4. Provide templates that follow style guidelines

If your colleagues make mistakes on standardized documents, then provide templates for them. For example, let’s say that you want them to use the ® mark on their first reference to the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index. Provide a template that includes “Standard & Poor’s® 500 Index” to spare them from thinking about the correct usage. Alternatively, you can ask them to start their new document from a cleaned-up version of the previous document.

5. Start a buddy system

It’s hard for most writers to catch their own mistakes. Consider starting a buddy system, where your financial professionals check one another’s text before submitting it to marketing. Of course, during busy periods, such as quarterly reporting crunches, it may be hard for them to make time for this.

6. Offer “carrots”

Can you offer a reward to employees who improve their writing or meet certain standards? The reward could be something as simple as recognition in your employee newsletter.

7. Explain how style mistakes affect client service and acquisition

Your firm’s financial professionals may not understand how their mistakes affect your firm’s relationships with clients and prospects. Tell them.

First, if you let mistake-riddled work reach clients and prospects, you undermine your firm’s credibility. A firm that doesn’t care about blatant typos may show a similar disregard for the details of their portfolio accounting or financial plans. That worries clients and prospects.

Second, the need for extensive proofreading and copyediting delays the publication of your firm’s content. A relatively clean piece of content from a writer who consistently observes style guidelines can quickly earn the marketing department’s approval. On the other hand, a piece that’s riddled with errors requires more time and possibly multiple reviews, as editors struggle to fix it. This delays content from reaching the firm’s audience.

8. Use techniques from Switch

In Switch, by Chip and Dan Heath, the authors tackle a similar kind of problem, how to get employees to file their expense reports on time. The Heaths note that nagging emails don’t work. They may even reinforce the perception that everyone ignores the style guidelines. However, they have some suggestions. which I gathered from the end of their “Script the Critical Moves” chapter.

Learn from success stories

The Heaths suggest that instead you look at the people who are doing things right. What are they doing differently? In the expense example, “Maybe they’ve handcrafted a set of techniques for logging expenses as they occur, so there’s not a big pile left at the end of the month,” say the Heaths. “Get them to share their system with others.”

Make it easy for people to comply

Another tip: “Script the critical moves” to remove ambiguity that paralyzes people. This can be tough with issues of style. Perhaps it means that the marketing department asks writers to observe some clear rules, while tackling the tough rules itself during the proofreading process. Giving employees a simple checklist might achieve this.

Provide motivation

“Find the feeling,” suggest the Heaths. That could mean trading on your employees’ feelings for their colleagues. In the expense report example, the Heaths suggest telling people how their actions prevent a colleague from meeting her deadlines. “It may be easy to rationalize missing an administrative deadline, but it’s harder to rationalize letting down a co-worker who’s counting on you,” say the Heaths.

With style guidelines, employee lapses may handicap client services and sales personnel, in addition to marketing staff.

Highlight compliance

“Rally the herd,” say the Heaths, because “people are sensitive to social norms.” If you highlight employees’ compliance with guidelines, you’ll encourage others to follow. As they say, “No one likes to hear they’re underperforming their peers.”

9. Be realistic

You can’t achieve 100% compliance with your style guidelines. Your financial professionals have lots of other demands on their time. Also, it’s hard for most people to catch errors in their own work. A smart marketing department will proofread its writers’ work.

However, you can boost the quality of your colleague’s work by applying some of the tips discussed above.

What are YOUR best tips?

If you’ve tackled this challenge, please share your tips. I’m also interested in hearing from financial professionals about how marketers can make it easier for you to create high quality materials.

If you’re a marketer, you may also enjoy “Reader question: How can communicators manage difficult portfolio managers?”

Image courtesy of stockimages at FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Disclosure: If you click on the Amazon link in this post and then buy something, I will receive a small commission. I only link to books in which I find some value for my blog’s readers.