Read critically, or write badly

The two sentences below from Joe Moran’s First You Write a Sentence resonated with me. Trying to explain why bad sentences exist, he says:

The writer knew what she wanted to say, thought she had said it, and gave up reading and listening. To write well, you need to read and audit your own words, and that is a much stranger and more unnatural act than any of us know.

One problem is that what we as writers want to say is clear to us. As we skim what we’ve written, the mind fills in missing information and relationships between one sentence and another. As a result, we mistakenly think that all is well with our sentences.

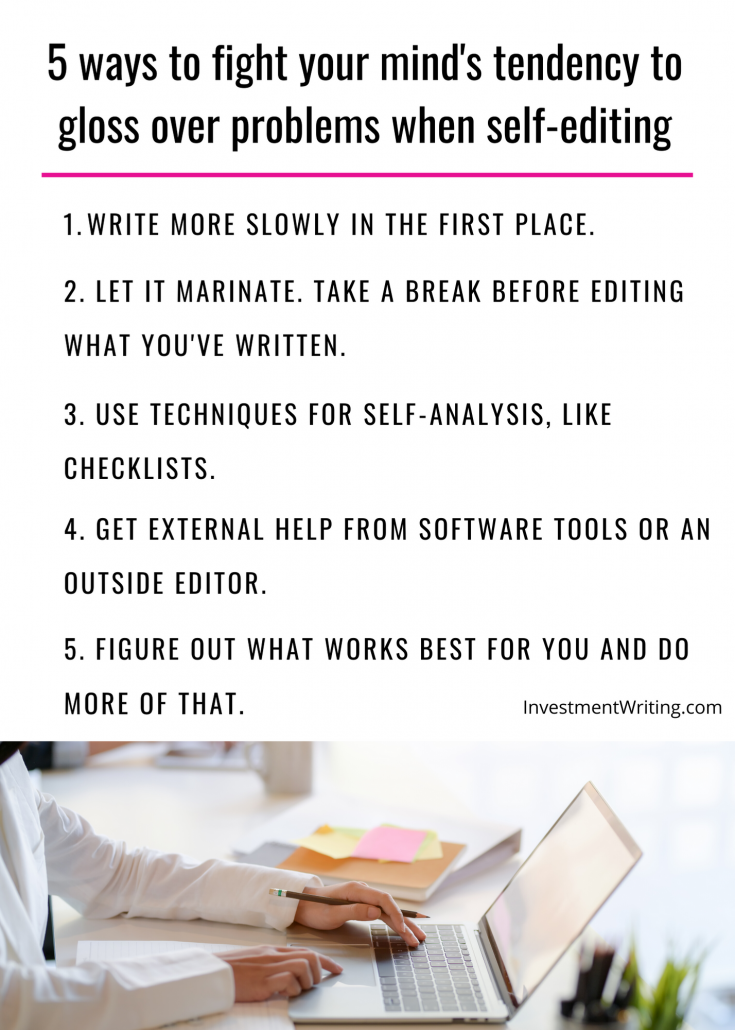

How can you fight your mind’s tendency to gloss over problems when editing your own writing? Below you’ll find one suggestion from Moran, and more solutions from me.

1. Write more slowly in the first place

Moran says:

Most of us, when we write, march too quickly on to the next sentence. To write intelligibly is hard enough, so be sure you have done that first. Fix your sights on making one sane, sound, serviceable sentence. As a farmer must do, hold your nerve and resist the impulse to put your energies into cash crops with quick returns. Have the confidence to leave fields fallow, to wait patiently for the grain to grow and to bear with the dry seasons.

Try his approach. You may enjoy it. If you’re like me, you’ll probably feel too pressured most of the time to write slowly. However, taking this approach sometimes is a nice change of pace.

2. Let it marinate

It’s hard to edit something immediately after writing it. I can catch some problems right away. Others take time to surface. This is why I sometimes write out posts by hand, and then scan and send them to my virtual assistant to input into a Word document or directly into WordPress. I do another round of editing after the posts have been typed.

I can see problems more clearly once the ideas have had time to marinate in my mind after I initially put them on paper. Some people call this approach “sleeping on it.”

Some of the problems I find are those Moran discusses when he explains how “A sentence can confuse in countless ways.” He points to small word choices with big, bad consequences:

Prepositions confuse because they so easily shapeshift into conjunctions or adverbs in the reader’s head. A poorly placed for or as is enough to lead the reader astray. Since can mean “because” but also “after that time.” While can mean “although” but also “during that time.” Prepositional phrases confuse if they are too far away from what they modify. I wrote my speech while flying to Paris on the back of a sick bag. Even over-correctness confuses. When you strain to avoid splitting an infinitive, believing (wrongly) that splitting one is wrong, it can draw attention to itself and give the reader pause.

Also, the time that passes since that writing allows me to read my work more objectively and sometimes inspires additional ideas.

With my “how-to” blog posts, I often write a bare-bones list of steps in my first draft. Then, I add flesh to those bones in the second draft.

3. Use techniques for self-analysis

To check whether my writing flows well from paragraph to paragraph, I use my first-sentence check for writers. If you read the first sentence of every paragraph out loud, can you understand the gist of your argument? If so, you pass the test. If not, you have work to do.

Another way to test your text, is to read it out loud. This is great for finding typos and other outright mistakes, as I’ve explained before. It also helps you to notice subtler problems with rhythm and arguments. Somehow, when you read out loud, it’s harder for the brain to fill in the missing pieces without noticing your writing’s weaknesses.

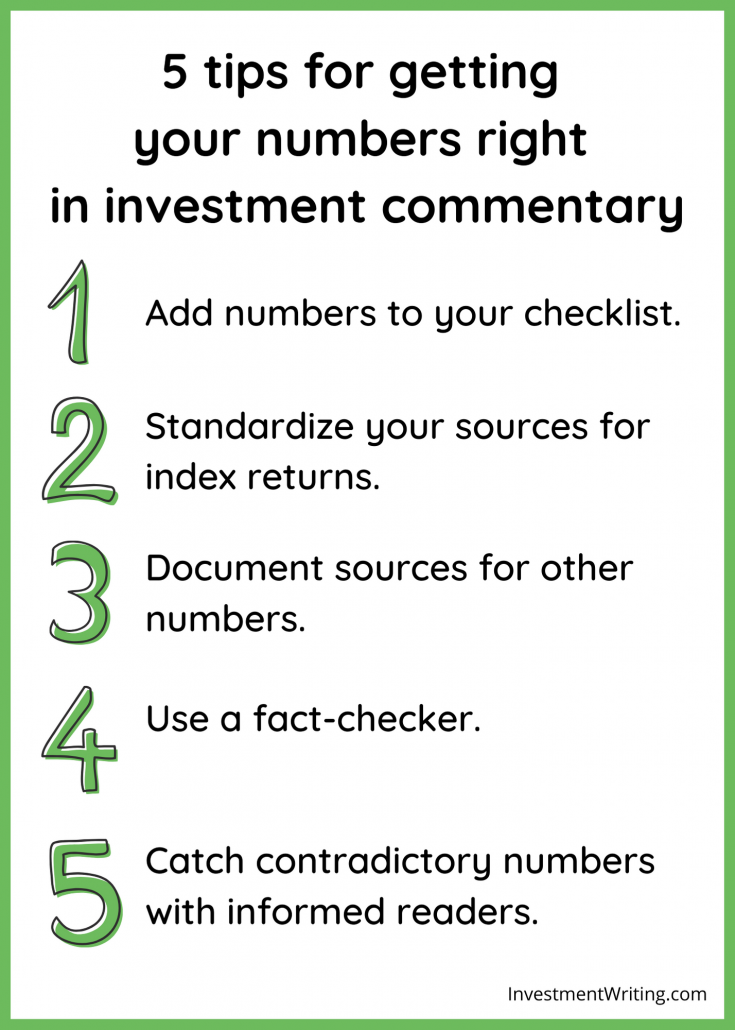

You can also create a checklist of your most common mistakes, and then check to see if those mistakes have snuck into the text.

You’ll find more tests sprinkled throughout my blog, including a technique for underlining your way to less financial jargon.

4. Get external help

Some automated help is available. For example, there are grammar and style tools, such as PerfectIt, that can check for basic mistakes. Hemingway goes beyond them to help you identify overly wordy writing. Some of my newsletter subscribers have told me that Hemingway has made a dramatic difference in their writing.

Alternatively, you can hire a professional editor to review your work. (Or, even hire a professional writer to write whatever you need.) As a writer-editor myself, I think that’s a great idea. Still, budgets don’t always permit outside help. And, you can’t hire a writer to write all of your communications.

Less expensive is getting help from non-professional writers. For example, you can ask for feedback from your colleagues or members of your target audience. As I’ve said elsewhere, don’t simply ask them, “What do you think?” or “Do you understand?” Instead, ask them “What is my main message, and can you explain it in your own words?” It’s easy for someone to parrot back your introductory paragraph. It’s much harder to explain it using their own words.

5. Figure out what works for you

Different techniques work best for different people—or situations. Experiment to see what works best for you.

Disclosure: If you click on an Amazon link in this post and then buy something, I will receive a small commission. I provide links to books only when I believe they have value for my readers.

The image in the upper left is courtesy of Studio GOOD Berliny [CC BY-SA 4.0].