No apostrophes in plurals!

Please stop using apostrophes to turn singular nouns into plurals. It’s wrong, but sadly common.

The plural of “client” is not “client’s,” it’s “clients.” “Client’s” is the possessive form of “client,” so it refers to something that belongs to a single client.

Why people are confused about apostrophes in plurals

I’m guessing that the confusion may have started with the rare style guidelines that call for using apostrophes to form plurals.

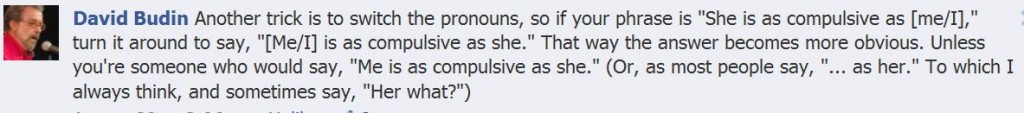

A Google search on using apostrophes to form plurals sent me to a post on the rule of adding an apostrophe to an acronym to form a plural on the website of Paul Brians, a professor of comparative literature at Washington State University. (Acronyms are words like AUM for assets under management or RIA for registered investment advisor.) However, he doesn’t cite a style guide as his source. He told me in an email that the Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) was his source. However, in my admittedly old CMOS, I found a reference to “CODs and IOUs” as correct (CMOS 6.9). That sent me searching for more information.

Grammarly’s article on apostrophe rules identifies a rare exception to the no apostrophes rule, but it’s different than what Brians says. This rule says to use an apostrophe to prevent misunderstanding the plural of lowercase letters. For example, to pluralize the letter i, write “i’s.” Otherwise, people will think you’re writing “is,” a form of the verb to be.

The goal of avoiding misunderstanding also lies behind a related rule from The New York Times. The newspaper doesn’t use apostrophes to pluralize acronyms, but it does use them for words like C.P.A. that include periods. According to the newspaper’s “After Deadline” column on “FAQs on style”: “Use apostrophes for plurals of abbreviations that have capital letters and periods: M.D.’s, C.P.A.’s.”

I have a quibble with that rule. Who still uses periods in CPA? The Association of International Certified Public Accountants uses CPA without periods on its webpage about the CPA designation.

By the way, The New York Times goes one step further than Grammarly on pluralizing individual letters. It applies the rule to uppercase letters: “Also use apostrophes for plurals formed from single letters: He received A’s and B’s on his report card. Mind your p’s and q’s.”

Apostrophes don’t pluralize proper names

Proper names are sometimes mistakenly pluralized by adding apostrophe plus s. That’s wrong.

Form the plural of most proper names by simply adding the letter s. One exception for proper names, as described by Garner: “those ending in -s, -x, or -z, or in a sibilant -ch or -sh, take es.”

Don’t use the grocer’s apostrophe!

The Grammarly article I cited above says that the mistaken use of an apostrophe is known as the “grocer’s apostrophe because of how frequently it shows up in grocery store advertisements (3 orange’s for a dollar!).” I bet you’ve seen many examples of this. I’ve featured some of them in my Mistake Monday posts urging people to proofread more carefully.

The bottom line: Most of the time, you form plurals by simply adding the letter s. The rare exceptions to this rule occur only when the lack of an apostrophe might confuse readers.

Note: I updated this post on Sept. 30, 2022.

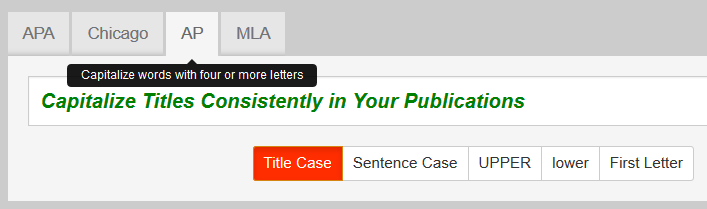

I’m a big fan of using sentence case for capitalizing titles. “Sentence case” means that you only capitalize the first letter of the first word of the title, just as you’d do in a sentence. This is easy to remember. Plus, it doesn’t require judgment calls about which words deserve an initial capital. That’s its big appeal in my eyes.

I’m a big fan of using sentence case for capitalizing titles. “Sentence case” means that you only capitalize the first letter of the first word of the title, just as you’d do in a sentence. This is easy to remember. Plus, it doesn’t require judgment calls about which words deserve an initial capital. That’s its big appeal in my eyes.