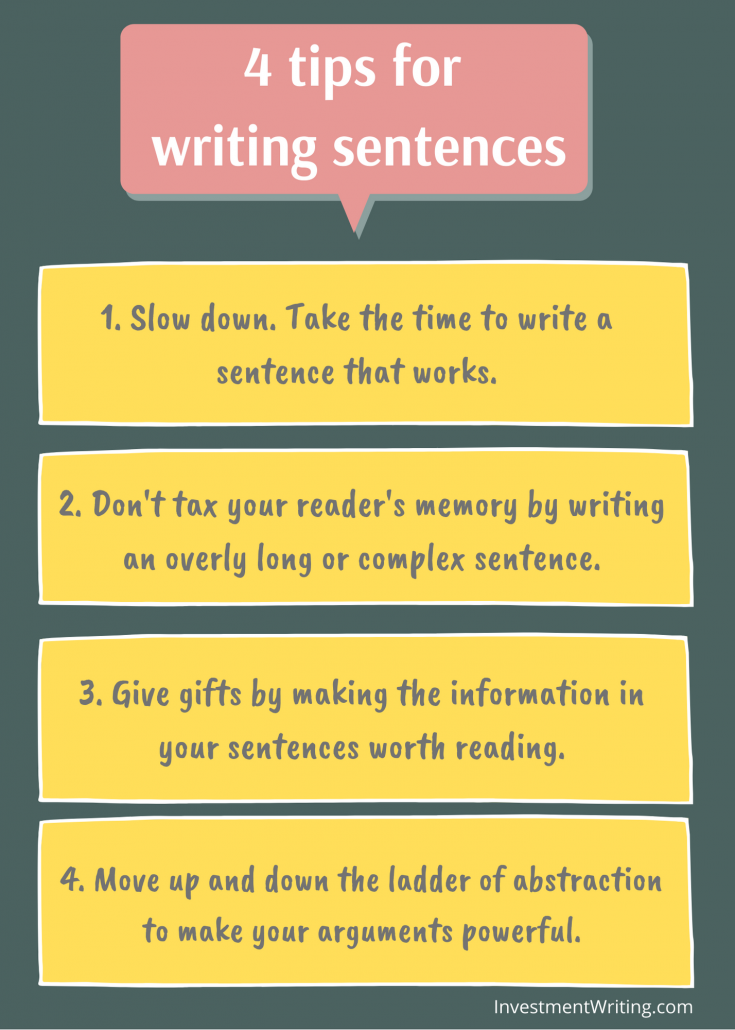

4 great tips for writing sentences

Joe Moran’s First You Write a Sentence has some great sentences about sentences.

Here’s a sampling of them, sorted by the lesson they suggest.

1. Slow down

Moran writes:

Most of us, when we write, march too quickly on to the next sentence. To write intelligibly is hard enough, so be sure you have done that first. Fix your sights on making one sane, sound, serviceable sentence. As a farmer must do, hold your nerve and resist the impulse to put your energies into cash crops with quick returns. Have the confidence to leave fields fallow, to wait patiently for the grain to grow and to bear with the dry seasons.

What a great analogy with farming!

I don’t recommend pausing after every sentence. After all, too many people struggle to complete a first draft. But, at some point, you should pause to review what you have written. Don’t hesitate to throw it out and start over if it doesn’t work. Your second draft is bound to benefit from the ideas “marinating” in your head.

2. Don’t tax your reader’s memory

“A sentence must stick in the mind. It has to be literally memorable, never so intricate that it cannot be absorbed all at once,” says Moran.

He also says:

The limit of a spoken sentence is the breath capacity of our lungs. The limit of a written one is the memory capacity of our brains. The full stop at the end of a sentence sets the limit. By the time it arrives, you must still be able to recall the sentence’s beginning. If you can’t keep it all in your head, then maybe those words weren’t meant to be together.

“Maybe those words weren’t meant to be together” agrees with my assessment of many complex, long sentences that I read in the fields of investment and wealth management.

I like using the idea of “memory capacity” to explain why many long sentences don’t work. I think that some of my clients might understand that better than my babbling about “too many dependent clauses.”

Complex sentences and paragraphs are also a problem when key information is unintentionally omitted. As Moran says, “A readers should not be asked to do the equivalent of lining up all the screws and dowels and puzzling over the instructions, only to find that the Allen key is missing.” Ooh, there’s another analogy that makes me smile.

3. Give gifts

Moran says that writing should be “an act of generosity, a gift from writer to reader.” So, follow the rules of good gift giving. For starters, “the gift should never feel like more trouble than it is worth.” Moreover, “the gift of knowledge that a sentence brings should never have to be bought, as it often is, with the reader’s boredom or confusion.”

Despite Moran’s suggestions, confusion abounds in many examples of financial writing. That’s no gift.

4. Move up and down the ladder

Moran uses S.I. Hayakawa’s idea of a ladder of abstraction. Concrete nouns like “chair” and “wall” are on the lowest rung. Abstract nouns—nouns like “truth” or “knowledge”—are on the top rung.

Moran says:

Writing stuck on one rung of the ladder of abstraction is too monotone. Arguments that use only abstract nouns, like truth and power and knowledge, are hard to care about because writing that sidesteps the senses is dull. Sentimental or pious writing also leans on abstractions, replacing difficult feelings with consoling simplifications. When words are too general, they paint inadequate pictures. But writing that describes only the feelable things in front of our faces is also dull, because it does not say why those things should matter to someone else. Writing stuck on the ladder’s middle rungs is worst of all, because here sit words with an illusory concreteness. Keep shinning up and down the ladder, though, and the reader gets the gist in different ways. She grasps big ideas through concrete things, and concrete things through big ideas. The tangible ignites the elusive and both of them shine brighter.

Moran himself seems to have a flair for “shinning up and down the ladder.”

I had to return this book to the library before finishing it. I’m definitely re-reserving it. It’s worth reading all the way through.

Disclosure: If you click on an Amazon link in this post and then buy something, I will receive a small commission. I provide links to books only when I believe they have value for my readers.