I often edit book reviews for the monthly magazine I edit for an audience of financial advisors. As a result, I’ve been thinking about what separates the best book reviews from the serviceable book reviews.

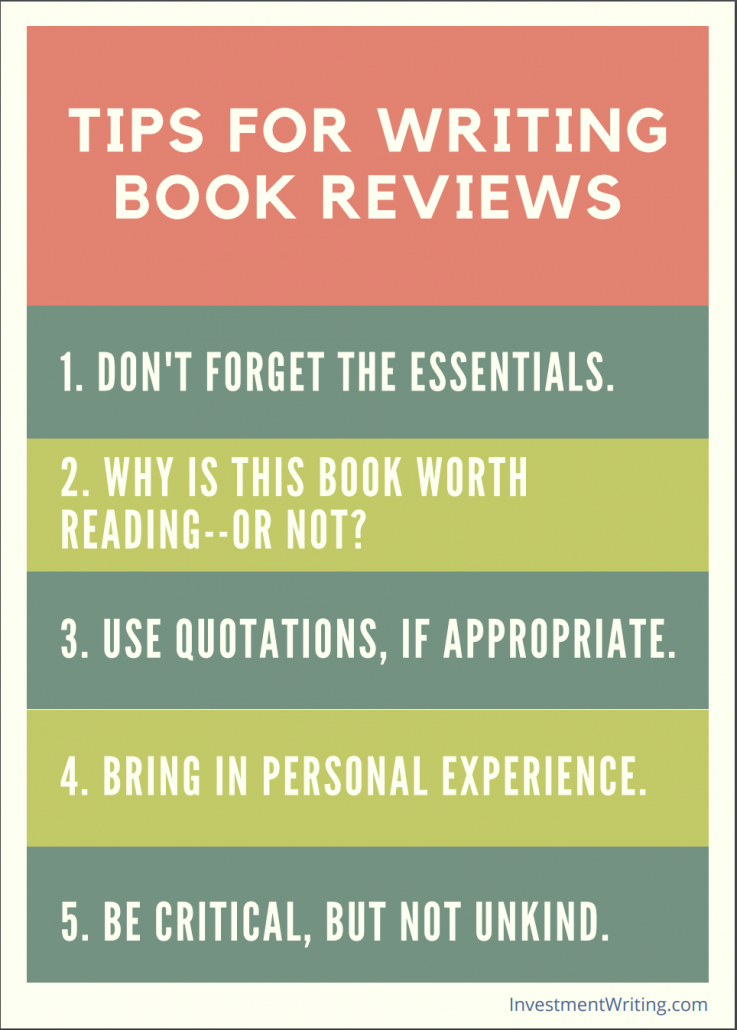

1. Don’t forget the essentials

Your readers will seek a brief overview of the book. You don’t need to regurgitate the table of contents. In many cases, a line or two will suffice.

Also, give the names of the author(s), the book, and the publisher. That’s all information your readers will need if they want to buy the book. Your readers may also appreciate the book’s list price so they know if it’s in their budgets, and a link for buying it.

When I send my contributors a template for their reviews, it includes a fill-in-the-blanks sentence with the information I want. I italicize [Book Title] because that’s the magazine’s style for book titles.

[Book Title] is published by [publisher] at a list price of $___. It is also available as an e-book.

2. Why is this book worth reading—or not?

Sometimes a book is worth considering because of reasons like the following:

- The author is a respected expert or has a strong background in the topic

- The book covers a hot topic

- The book promises a solution to a pressing problem

- Other people have said great things about the book

While the factors above make it worthwhile for someone to read and evaluate, the actual book may not live up to its promise. For me as a reader, the value of a nonfiction book depends on:

- Does it solve a problem for me?

- Does the book deliver what it promised?

- Is it written well enough that it’s not painful to read?

Your approach to your review may vary according to your background and the audience for your review.

For example, if you’re a financial advisor reviewing a book for a magazine aimed at financial advisors, then look at the book through the eyes of a financial advisor. This means that a book that’s great at educating individual investors on using educational savings accounts may not teach advisors anything new. On the other hand, advisors may benefit from recommending the book to their clients.

Similarly, a technical book on trusts or taxes might bore individuals, but become an invaluable reference for advisors. One of the valuable things you can do as a reviewer is to identify the audience for which a book is best suited.

Provide specific examples of what makes the book worthwhile. This means that you don’t simply say, “This book provides great ideas for turning spendthrifts into savers,” although that’s a great start. Give an example of a specific idea, and why or how it works.

Other potential topics could include the following, some of which I drew from “How to Write a Nonfiction Book Review” from Lesley Ann McDaniel’s blog and “Book Reviews” from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill:

- What did you like most (or least) about this book?

- What would you have done differently in tackling the topic?

- Are there other books that cover this topic better?

- Did the author’s argument persuade you?

3. Use quotations, if appropriate

Sometimes a good quotation from a book can drive home the point you want to make. But choose carefully. Rather than quote a clunky sentence, consider paraphrasing.

4. Bring in personal experience

If you’re a financial advisor writing for an audience of financial advisors, readers will be interested to learn your personal perspective. For example, you might say something like “the next time I face this [specific problem], I’m going to experiment with author’s suggestion to …”

On a similar note, you could say something like, “As a financial advisor, I wish the author had said more about …, but clearly that’s out of his scope as a writer for a general audience.” Or, “I’ve tried the technique the authors suggest, but until I read their book, I didn’t realize what I was doing wrong.” That bit of vulnerability lends authenticity to your review.

Of course, make it clear whether you recommend the book to your readers.

5. Be critical, but not unkind

Of course, sometimes a book doesn’t live up to its promise. You don’t have to praise a book that doesn’t deserve it.

On the other hand, don’t be mean. When I was learning how to critique my writing students’ work, I was told to “criticize the writing, not the person.” That’s great advice in any setting.

Another resource

I like the suggestions in “How to Write a Compelling Book Review” on the Oxford University Press’ blog. One of the tips that stood out for me was “Summary, however it is handled, should be combined with your evaluation of the book.” You’re writing a book review, not the kind of unopinionated book report that I had to write back in middle school.

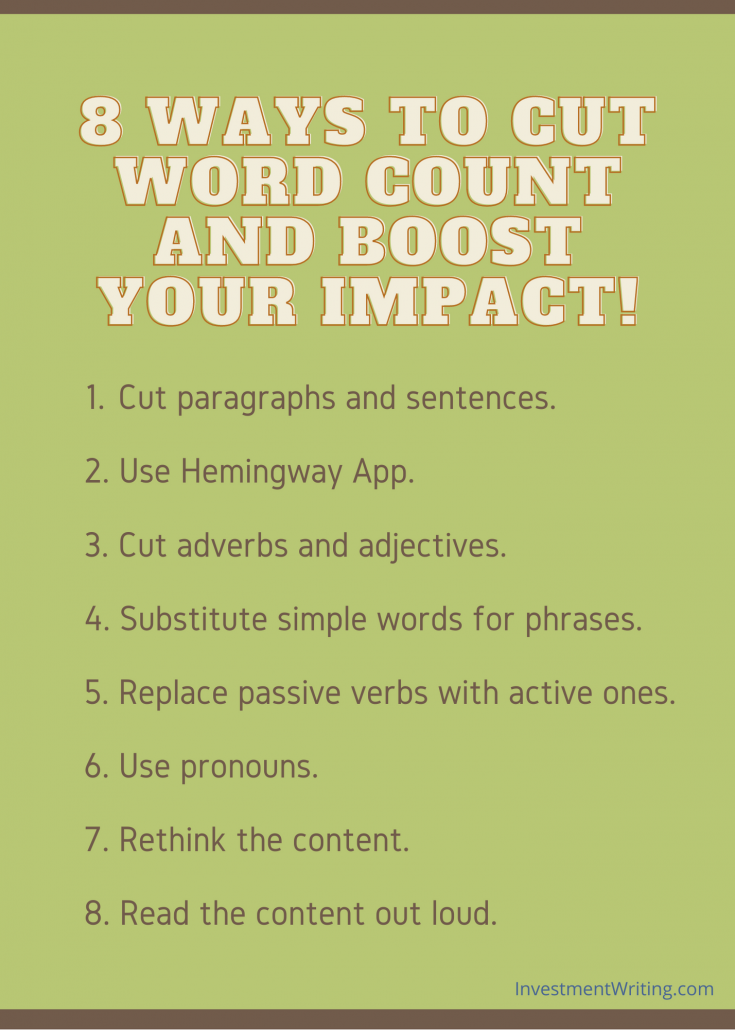

The image in the upper left corner has this attribution: Review by Nick Youngson CC BY-SA 3.0 ImageCreator