Here are some of the books that I enjoyed reading during 2022.

Writing

Actually, the Comma Goes Here by Lucy Cripps.

The Plain English Approach to Business Writing by Edward P. Bailey—This book offers sound suggestions for good writing.

By the way, if you want to improve your financial writing, check out my book, Financial Blogging: How to Write Powerful Posts That Attract Clients. Although it focuses on blogging, it teaches you a process you can apply to any type of writing.

Aging/health/transitions

Breaking the Age Code: How Your Beliefs About Aging Determine How Long and Well You Live by Becca Levy—I discuss this and two other books in this section in my November “From the Editor” column in the NAPFA Advisor.

Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life by Louise Aronson

Never Pay the First Bill: And Other Ways to Fight the Health Care System and Win by Marshall Allen—This book offers lots of suggestions for containing health care costs. For a taste of his advice, check out “When My Teenage Son Went to the Emergency Room He Put a Limit on What He Agreed to Pay.”

Stupid Things I Won’t Do When I Get Old by Steven Petrow

Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Changes by William Bridges—I was interested to read how there’s usually an extended period of transition.

What color is your parachute? for retirement: planning a prosperous, healthy, and happy future by John E. Nelson and Richard N. Bolles

Food

Bittman Bread: No-Knead Whole Grain Baking for Every Day by Mark Bittman and Kerri Conan—Since reading this book, my sourdough baking has switched to mostly using whole wheat flour. I love the scallion pancake recipe in this book, which I often make with chives from my garden. I also make Kerri’s sandwich loaf and whole wheat focaccia.

Flour: A Baker’s Collection of Spectacular Recipes by Joanne Chang and Christie Matheson

How to Cook Everything: 2,000 Simple Recipes for Great Food by Mark Bittman

King Arthur Flour Whole Grain Baking: Delicious Recipes Using Nutritious Whole Grains by King Arthur Flour

Race

I received four of these books through The Wall Street Journal’s free book program, which I wrote about in my September 2022 e-newsletter.

Black Food: Stories, Art, and Recipes from Across the African Diaspora, edited by Bryant Terry

Dorothy Dandridge by Donald Bogle

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers—This is fiction, but it says a lot about race.

The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography by Sidney Poitier—It was interesting to read this around the same time as Harry Belafonte’s memoir and the Dorothy Dandridge biography because they all knew and worked with one another.

My Song: A Memoir by Harry Belafonte and Michael Shnayerson

Raceless: In Search of Family, Identity, and the Truth About Where I Belong by Georgina Lawton

South to America: A Journey Below the Mason Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation by Imani Perry

Self-improvement

Better Each Day: 365 Expert Tips for a Healthier, Happier You by Jessica Cassity—This isn’t a book you’d sit down to read straight through. But it might be useful if you’re looking for a few small tweaks to make in your life.

Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle by Emily Nagoski and Amelia Nagoski

Find Your Unicorn Space: Reclaim Your Creative Life in a Too-Busy World by Eve Rodsky

Getting to Yes with Yourself by William Ury—This is a very sensible book by a renowned negotiator.

Getting to Yes with Yourself by William Ury—This is a very sensible book by a renowned negotiator.

Making Space, Clutter Free by Tracy McCubbin

The Power of Fun: How to Feel Alive Again by Catherine Price

The Power of Voice by Denise Woods

Fiction

These are several of the fiction books that I enjoyed this year.

Except the Dying by Maureen Jennings—This is the first of the Detective Murdoch mysteries that form the basis of the Canadian TV series. I find it relaxing to read well-crafted mysteries like this.

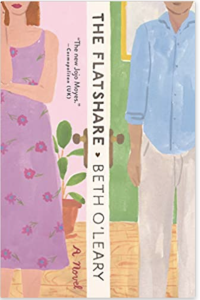

The Flatshare by Beth O’Leary—This was very entertaining.

The Flatshare by Beth O’Leary—This was very entertaining.

Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge

The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid—I also read Malibu Rising by the same author. I enjoyed both books, so I’ll probably read more by this author.

Disclosure: If you click on an Amazon link in this post and then buy something, I will receive a small commission. I provide links to books only when I believe they have value for my readers.