Publishing investment and financial content isn’t just for the big names any more. In the old days, only chief investment officers and senior executives put their names on articles published by investment, wealth management, and financial planning firms. This was true even when junior employees, marketing communications staff, or freelancers did the writing. Today, the needs of search engine optimization, social media and blogging, plus the demand for more personal, less bland content are changing the rules. Firms are asking more employees to write for their blogs, newsletters, and other publications.

This creates challenges, as well as opportunities, for financial firms. How can they engage more employees in writing for publication? How can they ensure that the content is good enough?

Most financial services employees aren’t hired for their writing skills. Some are gifted idea generators and wordsmiths. Others don’t enjoy writing and haven’t been trained to write well.

I have suggestions on how to inspire your employees to write more and better. If you need practical help right away, send your employees to my webinar on “How to Write Investment Commentary People Will Read,” scheduled for June 22, 2015 (Early Bird rate ends June 3).

1. Set a good example at the top

Employees notice senior executives’ actions. When your executives publish regularly, they set a good example for the rest of the firm.

Senior management can also help by recognizing the contributions of their juniors. Recognition can take many forms:

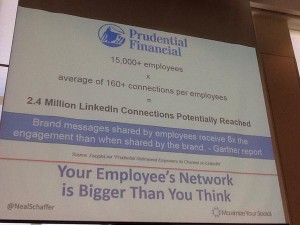

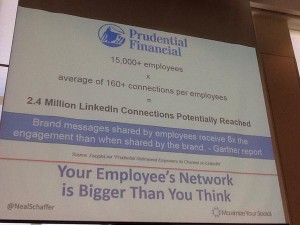

- Sharing content on social media—by the way, don’t underestimate the value of you and your employees sharing on social media, as my photo from social media expert Neal Schaffer’s May 7, 2015 presentation shows.

- Praising individuals for their contributions

- Featuring contributions by junior employees, as well as senior management, in a newsletter or blog

- Including writing as part of job descriptions and performance reviews

2. Offer ideas to jumpstart employee writing

Some people, even veteran writers, get stuck at the stage of generating ideas or starting to put words on the page. You can help them by suggesting topics or providing models for their pieces.

A. Suggest specific topics

When you suggest topics, try to be as specific as possible, especially if you’re helping a new writer. Instead of suggesting the broad topic of “market timing,” you might suggest

- Why market timing isn’t right for retirees

- Market timing or buy-and-hold—which is best?

- Three reasons why market timing doesn’t work

- Research shows benefits of market timing

A narrower suggestion gives your direction to your newbie writers. Of course, it requires you to have some knowledge of the topic so you don’t steer them wrong.

B. Provide models

Facing a blank page can intimidate writers at all levels of experience. To relieve their stress, provide your writers with models to follow. Give them examples of articles that you like. The examples can be from your firm or elsewhere. I provide one fill-in-the-blanks model on my blog.

3. Train your employees to write

Click on image to register

Training can help your employees to overcome their fear of writing and to write better and faster. I train corporate clients and members of professional societies to write better. However, any kind of writing class, even at a local education program can help. I got much of my early training in programs offered by the Boston, Cambridge, and Newton adult ed programs.

If you’d like online training, check out my webinar on “How to Write Investment Commentary People Will Read.”

It’s also good to provide training about compliance rules. For example, writers can’t guarantee returns or promise that certain things will happen. Also, some topics, especially discussion of specific products, may demand disclosures. Consider providing your employees with compliance checklists so they avoid violating compliance rules.

4. Provide editing and proofreading

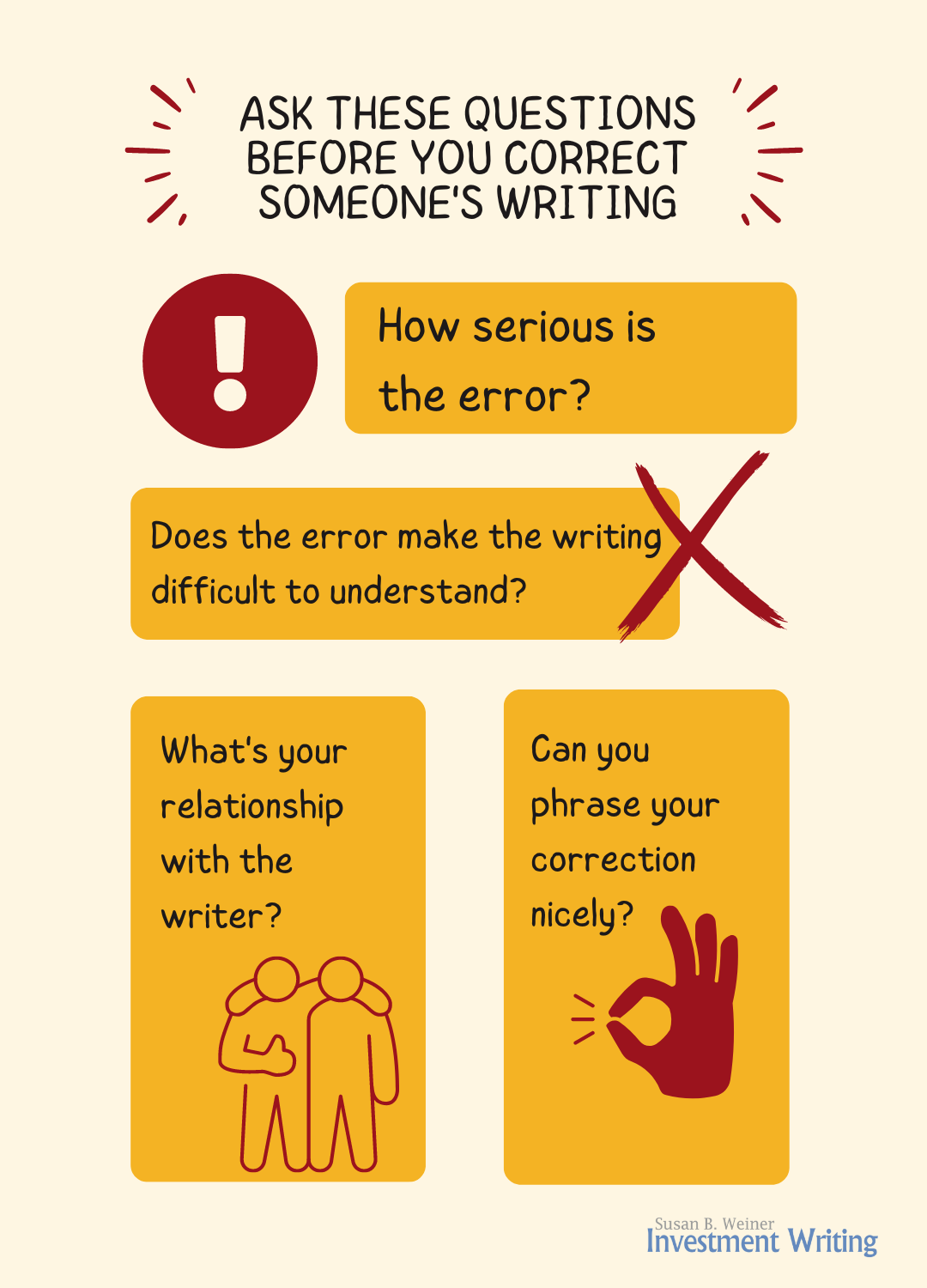

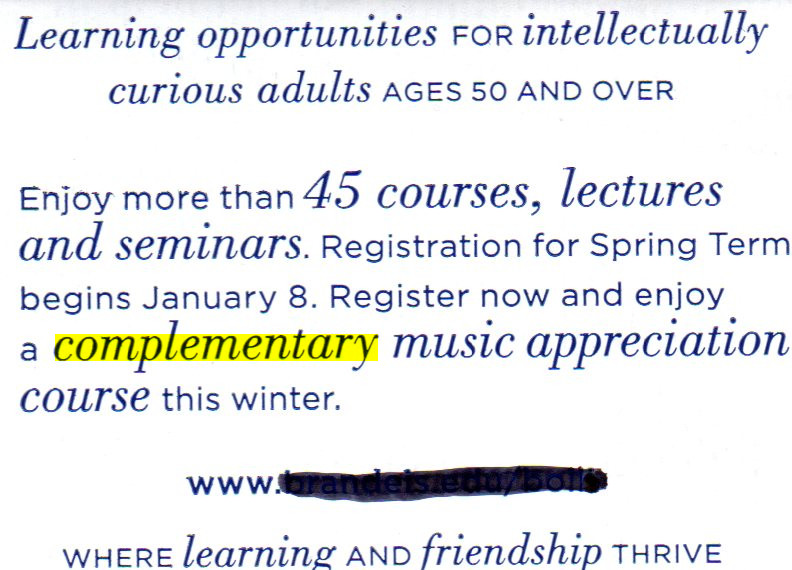

Typos and other mistakes undercut the credibility of your content. It’s hard for most writers to proofread themselves. This is why I suggest you use a proofreader-copy editor.

If your budget permits, hire a professional proofreader-copy editor. This could be someone in your marketing department or a freelancer. If it’s a freelancer, think about whether you want someone with financial expertise who can catch content problems. If your budget is tight, go for someone who only knows grammar and usage.

5. Reward participation

Employees like to do things that are rewarded and praised. When you recognize the contributions of your employee-writers, you’ll encourage more participation.

YOUR thoughts

How do you encourage your investment or wealth management professionals to write? Please tell me.

Image courtesy of Stuart Miles at FreeDigitalPhotos.net