What’s too long for a blog post? I stirred up a lively conversation when I posted this question on social media earlier this year. I asked because I’d drafted a 2,400-word blog post. That’s unusual for me. My natural length seems to be 400 to 600 words, although I’ve written longer.

As I expected, there’s no consensus on the perfect blog post length. However, you can make the decision that’s best for you, if you understand the issues.

The case for blog posts running 2000+ words

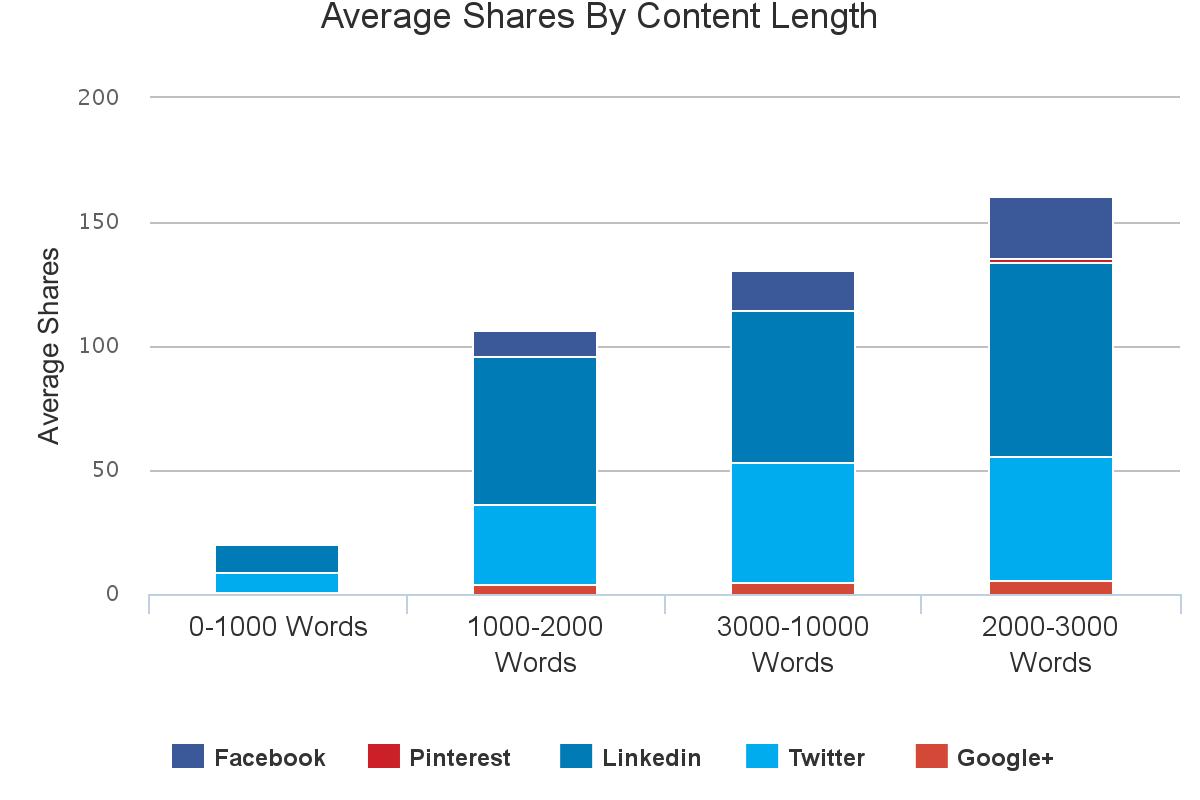

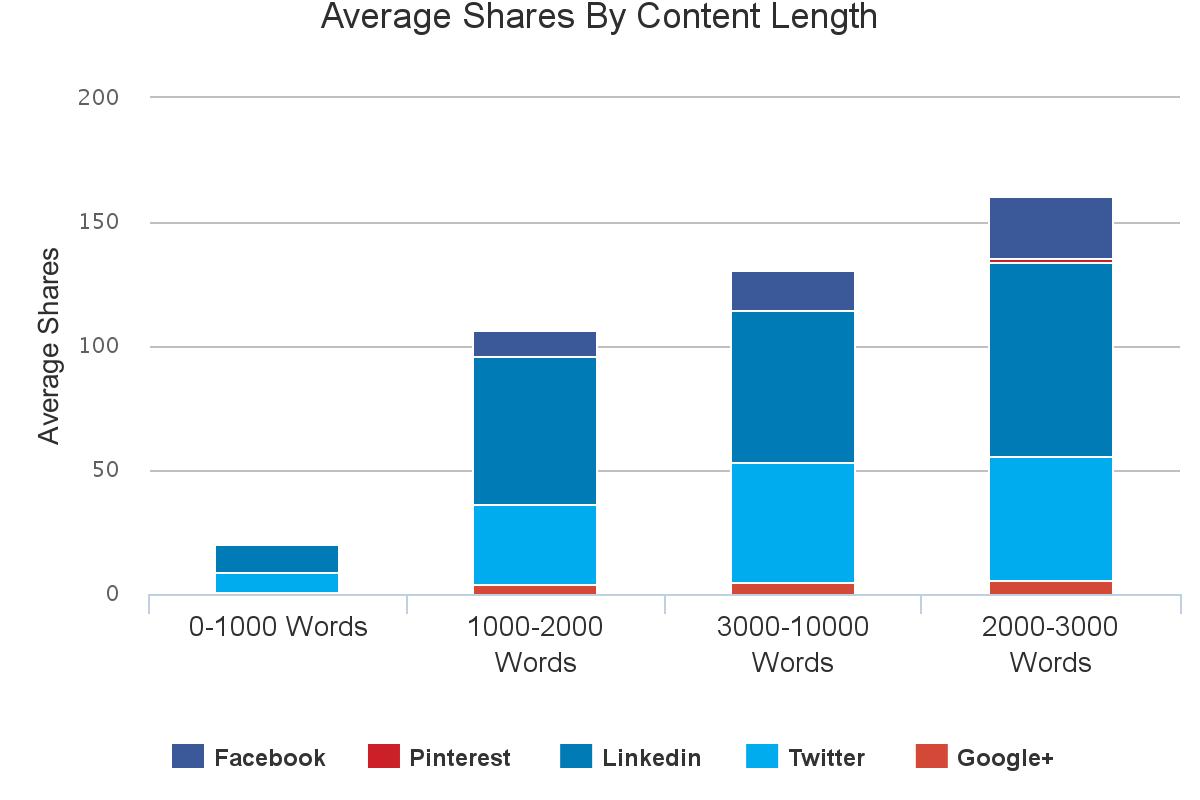

Long posts do best, as measured by shares and links. That’s what BuzzSumo-Moz research on content—that’s content of all kinds, not just blog posts—suggests, as reported in Contently’s “5 Ways Content Goes Viral.”

“Long” means way longer than the typical blog post. It means 2,000 words or more. To put that in perspective, according to Contently, “After studying close to 490,000 text-based articles, BuzzSumo and Moz found that 80 percent of content contains fewer than 1,000 words, while only 2.5 percent surpasses 3,000 words.”

The difference between shorter and longer content was dramatic. Content with less than 1,000 words averaged about 3.5 shares apiece vs. almost nine shares for content with 2,000 to 3,000 words, and 11 shares for 3,000+ words.

Evidence from financial blogger Michael Kitces

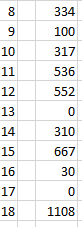

When I think about long blog posts, I think about Michael Kitces, who writes the Nerd’s Eye View blog. He shared the following graph with me, showing that long content dominates his shares. In fact, 2,000 to 3,000 words is his perfect blog post length.

Michael Kitces’ share counts by article length. Image courtesy of Kitces.com

Here’s what Michael said to me in an email exchange about longer blog posts:

I’ve found that optimal length seems to be in the 2,000 – 3,000 word range.

We often say that people “don’t have time” to read long posts. And I suppose technically that’s true. Most people don’t. But people who have REAL problems, need REAL solutions, and might want to HIRE you, are the ones who are motivated enough to actually read a long post. And get interested. And do business with you.

So think of it this way: writing long and thorough posts is a great screening process, because it helps to ensure the people who read it are interested enough to potentially do business with you.

That’s an intriguing point about your best prospects being willing to read your long posts.

An earlier Investment Writing take on blog post length

For another perspective on blog post length, read this guest post on my blog “Do longer articles really get shared more often?”

Reasons you shouldn’t go long

1. Sharing isn’t the same as reading

If you’d like people to read your content, rather than simply sharing it, shorter may be better. When people share your content, they may not have read it from start to finish. I’m living proof of that.

I confess that I’ve shared articles that I haven’t finished. Why? Because I’ve found an article that I believe will interest my followers, but it isn’t that useful to me. I read enough to find worthy content and then I skim the rest to get a sense of whether it upholds the standards of the beginning. If there’s one tip in the first part of the article that can help my connections move closer to achieving their goals, I figure it’s worth sharing.

When it comes to getting your readers through an entire post, shorter is better, unless the reader is motivated to learn about the topic you present. To support this, here are some of the comments I received in response to my asking if I should publish a 2,400-word blog post:

- I’ve been staying under 1000 for my site….a typical newspaper column used to be about 500

- Few blog entries I’ve edited were more than 550 words long.

- I think it’s too long!

Several respondents suggested breaking my blog post into two parts to make it more manageable. They also made the smart suggestion that I should structure a long post to make it easy for my readers to absorb.

2. You’re not good at writing long

Don’t write long blog posts if can’t do a good job on them. You need compelling insights or strong writing skills—or both, ideally. Without them, you’ll drive away the people whom you’re trying to attract.

One person who commented on my question said, “Long posts are better if well written.” Clearly they they don’t enjoy poorly written long posts. Who would?

3. Your topic doesn’t need a long explanation

If you emphasize length over content, you’ll end up with repetitive, boring blog posts.

Your content should be “long enough to make your point,” as one of the people who commented on my blog post length question. Don’t make it longer than that.

Short can work

What if you lack the skill or motivation to write long? Don’t give up!

Short can work.

In “How Long Should Each Blog Post Be? A Data Driven Answer,” Neil Patel shares the example of Seth Godin. Godin has been tremendously successful with short posts on his Seth’s Blog. At a quick glance, his posts generally run fewer than 300 words. Many run under 100 words.

Still, if you’re not a social media visionary like Seth Godin, consider writing longer than him. Yoast, which produces an SEO optimization plugin (to help you get found in online searches) suggests in “Common sense for your website” that you aim for a minimum of 300 words:

Your page content should contain at least 300 words. That has a simple reason: would your page be a great source for the topic or keyword you want to rank for when it would only contain 50 words? Is that all there is to say about that keyword? I don’t believe that, you don’t believe that and Google does not believe that. There should be a significant amount of content for your page to be considered a great source of information.

The perfect blog post length?

What’s the perfect blog post length? It depends. The answer will vary depending on your goals, the strength of your writing and information, and the time that you have to sink into writing.

I’m going to continue to average far fewer than 2,000 words per post, despite all the research about sharing. Shorter works for me, with some exceptions.

Speaking of exceptions, I published “My experiment blogging on LinkedIn,” the blog post that sparked this discussion, with a length exceeding 2,700 words.

Please tell me what you see as the perfect blog post length.

Blog image courtesy of Stuart Miles/ FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Rule #1: Do not quote ancient philosophers when the market is crashing.

Rule #1: Do not quote ancient philosophers when the market is crashing.

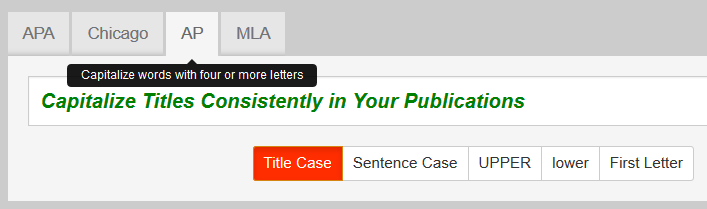

I’m a big fan of using sentence case for capitalizing titles. “Sentence case” means that you only capitalize the first letter of the first word of the title, just as you’d do in a sentence. This is easy to remember. Plus, it doesn’t require judgment calls about which words deserve an initial capital. That’s its big appeal in my eyes.

I’m a big fan of using sentence case for capitalizing titles. “Sentence case” means that you only capitalize the first letter of the first word of the title, just as you’d do in a sentence. This is easy to remember. Plus, it doesn’t require judgment calls about which words deserve an initial capital. That’s its big appeal in my eyes.

Grant’s interest in procrastination was inspired by one of his graduate students. “She told me that her most original ideas came to her after she procrastinated,” says Grant. He and his student tested whether her experience applied more broadly. Their experiments suggested that “procrastination encouraged divergent thinking.” Why? Because it gives us a chance to move beyond “our first ideas, which are usually our most conventional.”

Grant’s interest in procrastination was inspired by one of his graduate students. “She told me that her most original ideas came to her after she procrastinated,” says Grant. He and his student tested whether her experience applied more broadly. Their experiments suggested that “procrastination encouraged divergent thinking.” Why? Because it gives us a chance to move beyond “our first ideas, which are usually our most conventional.”