What if my financial article has too many examples?

Examples are great additions to your financial article or white paper. They make your points come alive, convincing your readers of your main points. However, your financial white paper can have too many examples.

For example, imagine an article that has 20 bullet-pointed examples of how a retirement account might help investors. I doubt readers will get beyond six bullet points at most. They may abandon your article because of information overload.

Sometimes it’s true that “less is more.”

How can you fix a financial article or white paper with too many examples? I have suggestions.

Solution 1: Delete examples from your financial article

Sometimes the simplest solution is the best. Identify the most compelling examples and delete the rest.

Don’t throw out those examples, which a small subset of readers may find powerful. Instead, “Save your trash to feed your blog,” as I’ve said before. You can write a narrowly focused blog post or article that addresses the examples cut from your original article.

Solution 2: Organize examples into subgroups

You may be able to organize your examples into subgroups. Imagine that you have 20 examples of the best retirement account choices. If you divide those examples into six categories, your readers can zoom in on the information that’s relevant to them.

For example, you might divide examples into the following categories in terms of whom they help. Categories might include retirement savers who:

- Are under age 50

- Are age 50 and up

- Are nearing the age of required minimum distributions

- Have maxed out their other retirement accounts

- Want to buy a piece of property as an investment

- Are more concerned about passing assets to future generations than saving for retirement

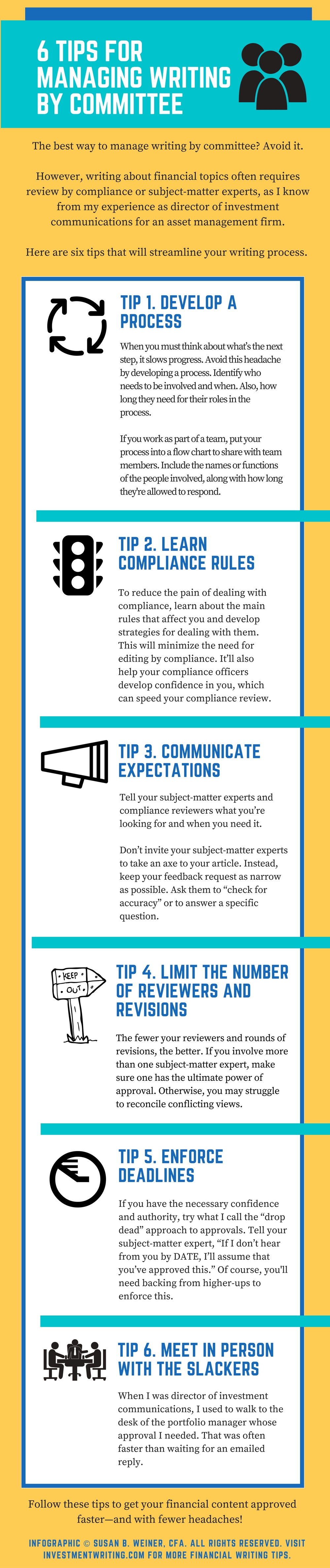

Solution 3: Create a chart, table, or other exhibit

Consider creating a chart, table, or other exhibit that organizes your examples. You can discuss the most compelling examples in the body of your white paper, but refer your readers to your exhibit for more information. The visual aspect of exhibits helps readers to focus on what interests them the most. It also helps them to absorb your information more efficiently.

Another possibility: Create a flow chart that points readers to different examples based on their individual situation and desires.

Exhibits break up the wall of words. Exhibits with more images, such as infographics, are also great for capturing attention on social media.

Solution 4: Dump examples in an appendix

If you can’t bear to edit or organize your examples, then put them in an appendix. There they won’t prevent readers from absorbing your arguments in the body of your white paper or article. Yet they’re available for people who want to review all the relevant information (and more) before making a decision.

Use these solutions and boost the power of your financial article, blog post, or white paper!

Image courtesy of Stuart Miles/Freedigitalphotos.net

Do you ever struggle to start your writing projects? I do. Although I’m a demon about completing my projects on time, sometimes writer’s block slows me. When that happens, a tool that I bought at a dollar store in Montreal often comes to my rescue. It’s a kitchen timer.

Do you ever struggle to start your writing projects? I do. Although I’m a demon about completing my projects on time, sometimes writer’s block slows me. When that happens, a tool that I bought at a dollar store in Montreal often comes to my rescue. It’s a kitchen timer. Sure, no one will protest if you add or delete a comma in a sentence. No one will even notice the difference between the mispunctuated “He said ‘Thank you’ ” and the correct “He said, ‘Thank you.’ ” You can even change “average annualized returns” to “annualized returns,” removing the redundant “average.” I think most people are fine with small tweaks that don’t change the meaning of the person who wrote or spoke the words.

Sure, no one will protest if you add or delete a comma in a sentence. No one will even notice the difference between the mispunctuated “He said ‘Thank you’ ” and the correct “He said, ‘Thank you.’ ” You can even change “average annualized returns” to “annualized returns,” removing the redundant “average.” I think most people are fine with small tweaks that don’t change the meaning of the person who wrote or spoke the words. Please stop talking about how great your content makes YOU feel.

Please stop talking about how great your content makes YOU feel.

Before: The company’s 2015 loss is a reflection of the shifting preferences of consumers for ordering online instead of going into a store to buy.

Before: The company’s 2015 loss is a reflection of the shifting preferences of consumers for ordering online instead of going into a store to buy.