How can I create a document that’s free of errors and consistent in its usage? When I accepted a job editing a magazine that said it uses AP style, I figured that AP StyleGuard software might be the answer to my prayers.

Does AP StyleGuard deliver? Yes and no. It has pros and cons.

The software doesn’t say that it’s one-size-fits-all for your proofreading needs. The features list on its website promises that it:

- Helps you to avoid using redundant words or over-used words.

- Helps you to catch capitalization and punctuation issues

- Catches style issues that escape the spell and grammar checkers in Microsoft Word

- Helps you to identify issues such as “Should this be one word, two words, or hyphenated?

- Provides common unit conversions within the document

- Provides possible abbreviations and checks for correct abbreviation rules.

Pros of AP StyleGuard

1. Automatic checking of compliance with AP style

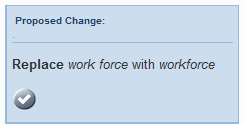

If you’re writing for an organization or publication that follows AP style, this software will automatically highlight your style mistakes. You can fix each mistake with a simple click, assuming that you agree with the software’s suggested correction. As you’ll see later, agreeing with the software’s suggested correction is an issue for me.

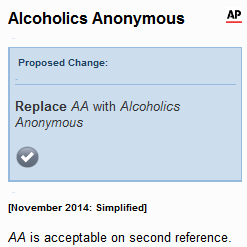

2. Access to the online version of the latest AP Stylebook

AP style changes over time. With an AP StyleGuard subscription, you always have access to the latest guidelines.

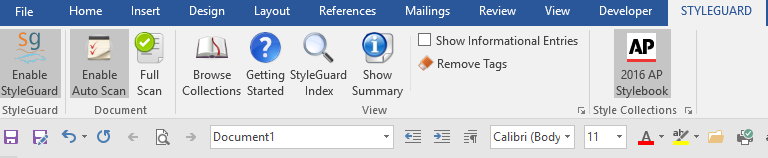

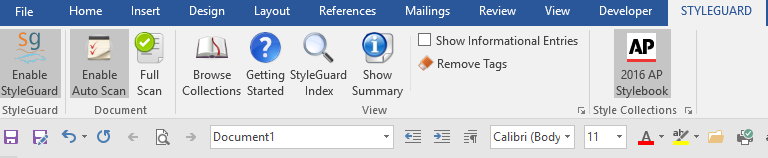

3. Integration with Microsoft Word

After installing the software on your computer, it appears as part of the ribbon at the top of your Microsoft Word documents.

What I like best about this software

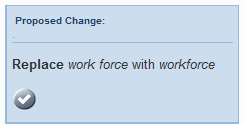

- In addition to helping me comply with AP style, it helps me to standardize my usage on topics such as whether to use “work force” or “workforce.

- I can eliminate excess spaces after periods with one click.

Cons of AP StyleGuard

1. Inability to customize for your publication’s style

The magazine that I write for uses a modified version of AP style. Our modified version includes using the serial comma and using the spelling “advisor” instead of “adviser,” which is preferred by AP. (I’ve blogged about the advisor vs. adviser debate).

As you can imagine, our practices trigger lots of false alerts in the software. I spend a lot of time clicking to ignore these style rules. Some software, including—I believe—AP Lingofy, let you customize your styles. PerfectIt Pro, software that I’ve used in the past, lets you create multiple style sheets. That could help writers like me who work with multiple clients with different style preferences.

2. Mistaken flagging of “mistakes”

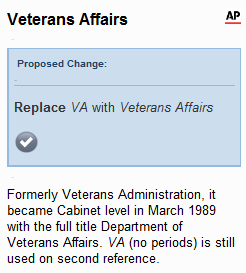

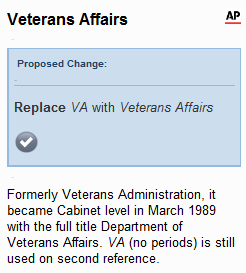

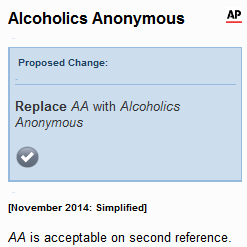

Whenever I write use “VA” as an abbreviation for “variable annuity,” the software scolds me that I should spell out “Veterans Affairs.” No, I won’t do it. I also have a problem when I write about AA-rated bonds.

3. Failure to catch some apparent style errors

The software doesn’t flag ever instance of what seem to me like style errors.

For example, the sentence below is inconsistent in how it uses an en-dash, an em-dash, and the space around those dashes. AP StyleGuard doesn’t see any problem with it.

But what else could you—or I – do?

The phrase “or I” should be set off by two en-dashes or two em-dashes—not one of each. And the spacing should be consistent.

4. Microsoft Word freezes

Microsoft Word freezes way too often when I have StyleGuard enabled. Also, it seems to mess with my ability to enter Microsoft Word Comments into documents. I have a fairly new, powerful desktop computer with Word 2016 so I don’t think my hardware is the problem.

I minimize my problems by enabling StyleGuard only when I’m actively using it in my proofreading. So, if I’m proofreading four documents, I enable and disable StyleGuard four times. Luckily, this can’t be accomplished with a simple click in the ribbon above my Word document.

4. Lack of grammar checking

AP StyleGuard is not a grammar checker. It found nothing wrong with the sentence “They is coming.”

On the other hand, the software doesn’t claim to be a grammar checker. It’s simply checking for consistency with AP Style. Sometimes inconsistencies are also grammar mistakes.

5. Annual fee

You must pay an annual fee for the software. Of course, it does include the updated version of the AP Stylebook. You do get something for your annual investment.

Will I renew?

Will I renew my subscription to AP StyleGuard? I’m not sure. If I think the Stylebook updates are worth it, I may look at Lingofy for its customization options.

On the other hand, I may consider going back to PerfectIt Pro or doing research on other alternatives. PerfectIt Pro is a one-time purchase, at least until they do a major revamp of the software.

What software do YOU recommend?

I’m curious to hear about your experience with proofreading, grammar, and usage software. What do you recommend—and why?

Image courtesy of stockimages at FreeDigitalPhotos.net.

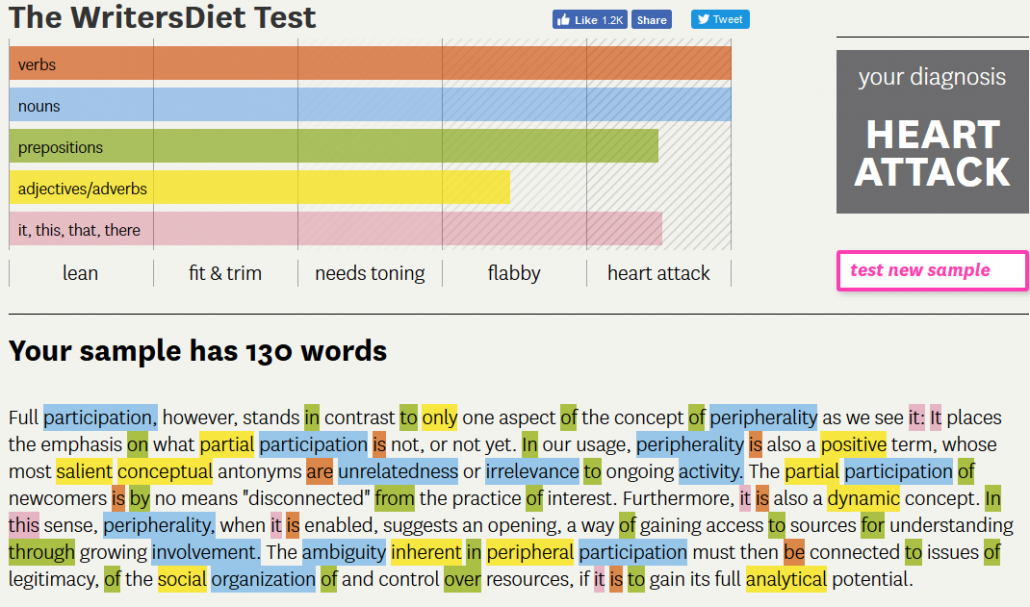

reverse is true, too. See the paragraph below, which I used as an example of bad writing in “

reverse is true, too. See the paragraph below, which I used as an example of bad writing in “