My 2017 reading, with book recommendations for you

Here are some of the books I read (or referred to) in 2017, divided by categories. The starred books are books that I refer to in 2017 blog posts, some of which haven’t been published yet.

Biography/autobiography

* Bossypants by Tina Fey

* Turner: the extraordinary life and momentous times of J.M.W. Turner by Franny Moyle

Elder care

I learned about the first two books in this section from New York Times columnist Ron Lieber’s article, “Hard-Won Advice in Books on Aging and Elder Care.” I imagine the other books he reviewed are equally good.

The 36-hour day: a family guide to caring for people who have Alzheimer disease, other dementias, and memory loss by Nancy L. Mace and Peter V. Rabins — This book has many practical tips.

A bittersweet season: caring for our aging parents—and ourselves by Jane Gross

Seven Steps to Managing Your Memory: What’s Normal, What’s Not, and What to Do About It by Andrew E. Budson and Maureen K. O’Connor — One of the authors spoke at my local library. I missed his talk, but the book seems solid.

Marketing

* Contagious: Why Things Catch On by Jonah Berger

* One Perfect Pitch: How to Sell Your Idea, Your Product, Your Business–or Yourself (Business Books) by Marie Perruchet

Personal finance

* Breaking Money Silence: How to Shatter Money Taboos, Talk Openly about Finances, and Live a Richer Life by Kathleen Burns Kingsbury

Reference books for writers

* Associated Press Stylebook by Associated Press

* Garner’s Modern American Usage by Bryan A. Garner — This has become a “go to” reference for me.

Words

Hemingway didn’t say that: the truth behind familiar quotations by Garson O’Toole

The Story of Be: A Verb’s-Eye View of the English Language by David Crystal — Before I read this book I hadn’t thought about the many meanings of the word “be.”

Writing

Do I Make Myself Clear: Why Writing Well Matters by Harold Evans

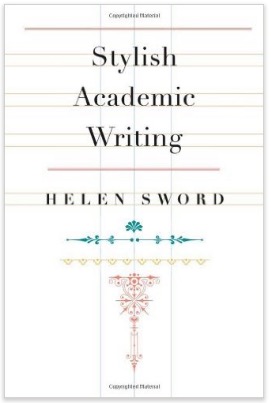

* Stylish Academic Writing by Helen Sword — This book was my favorite discovery in 2017.

* Unless It Moves the Human Heart: The Craft and Art of Writing by Roger Rosenblatt

Disclosure: If you click on an Amazon link in this post and then buy something, I will receive a small commission. I link only to books in which I find some value for my blog’s readers.

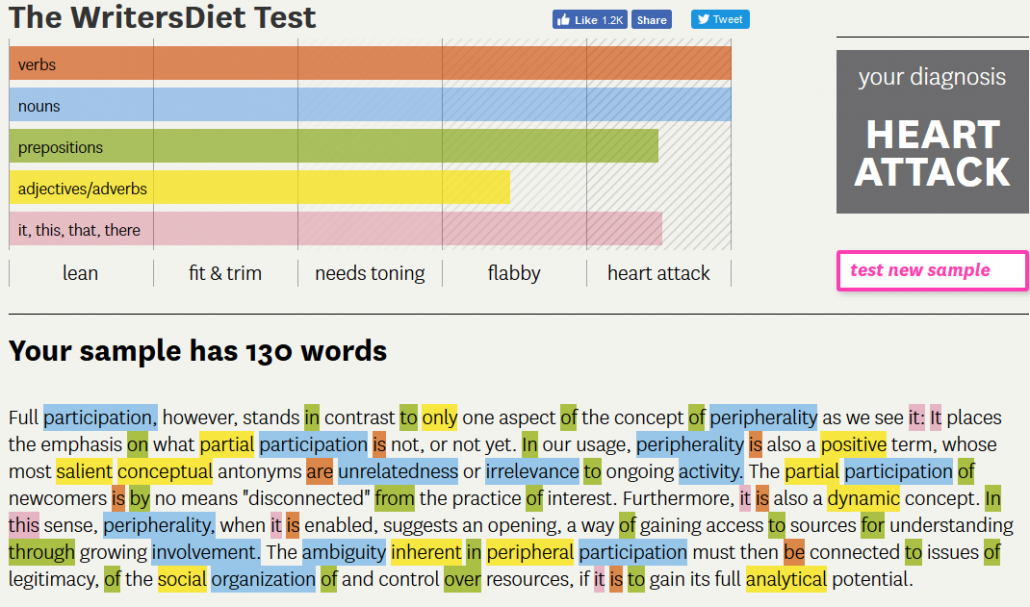

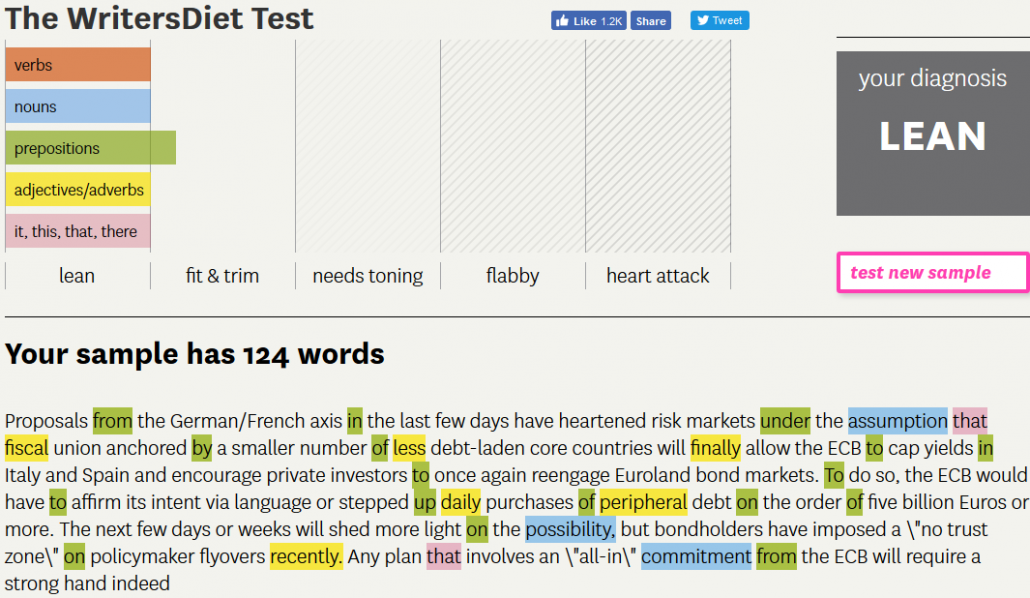

reverse is true, too. See the paragraph below, which I used as an example of bad writing in “

reverse is true, too. See the paragraph below, which I used as an example of bad writing in “