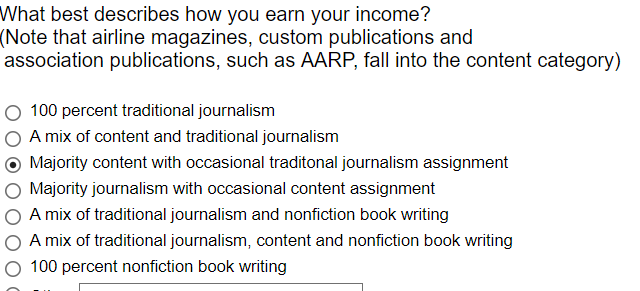

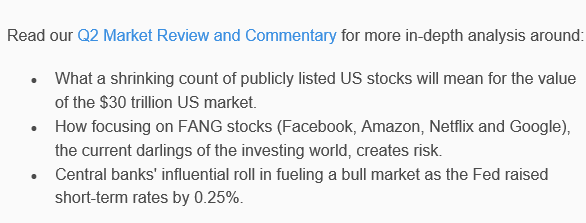

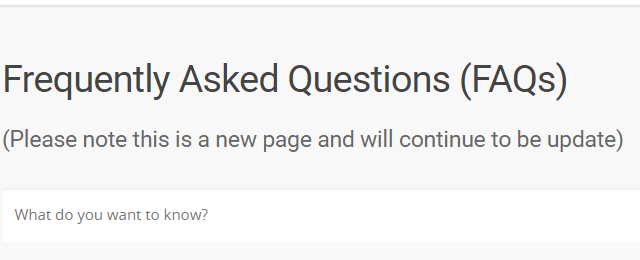

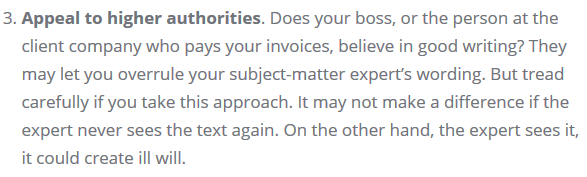

MISTAKE MONDAY for November 27: Can YOU spot what’s wrong?

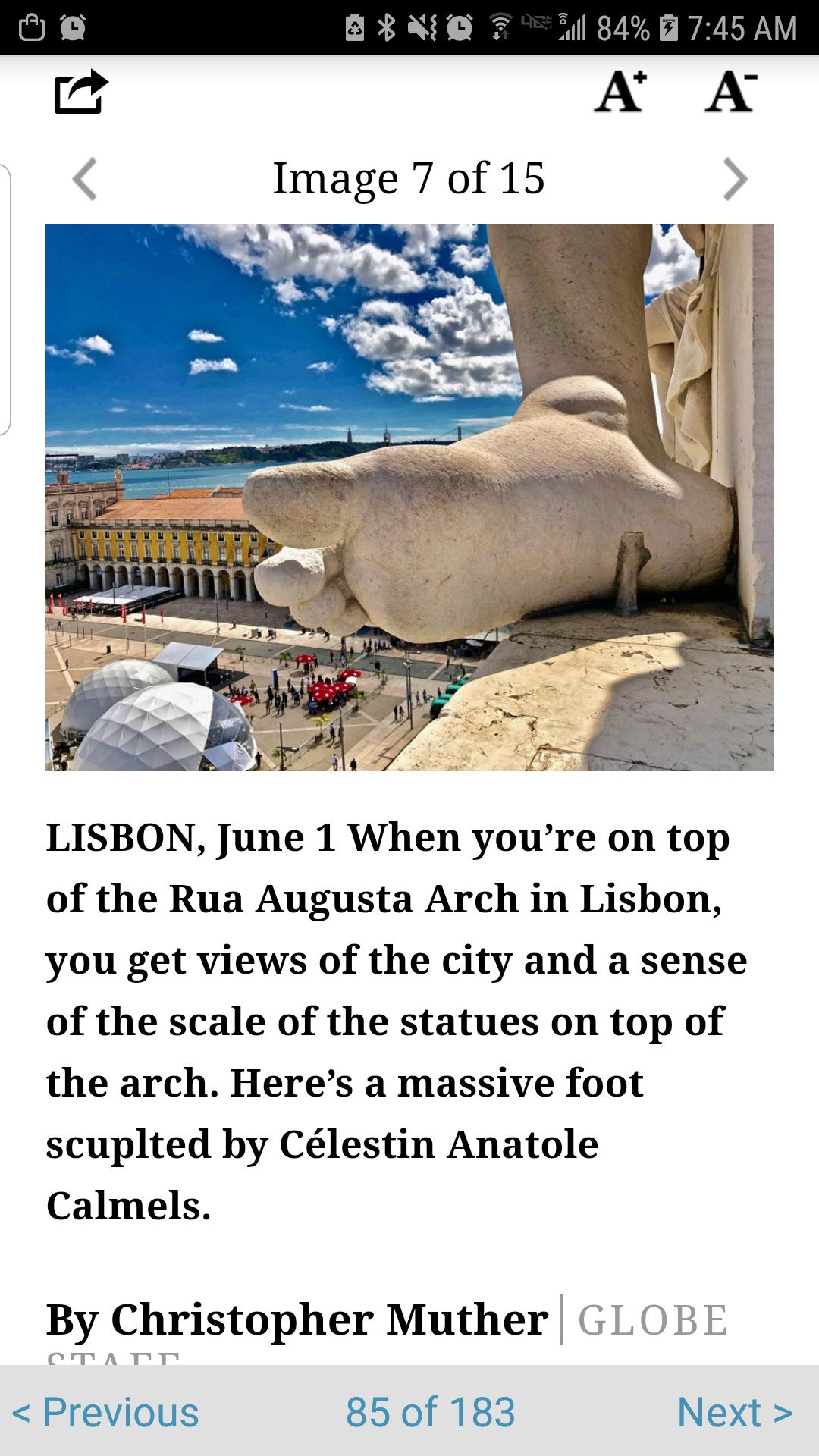

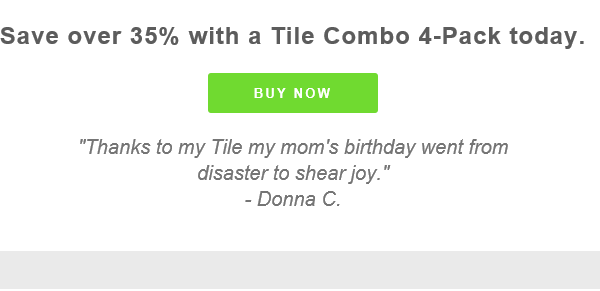

Can you spot what’s wrong in the image below? Please post your answer as a comment.

Oh, I felt so tempted to make a snarky comment about this mistake!

I post these challenges to raise awareness of the importance of proofreading.